The A2 freeway at Alleringersleben, somewhere in central Germany between Magdeburg and Braunschweig. This six-lane freeway is one of Europe’s most important west-to-east axes, connecting the major Dutch ports with the interior of the continent. It is a main artery of the European economy. As many as 22,000 trucks travel along this stretch of road every day, making it one of the places with the highest volume of traffic in the whole of the EU and a good example of the challenges that need to be overcome to bring alternative drives for long-distance freight transport trucks into the mainstream.

The shift to electric mobility across all of society cannot be achieved with electric cars alone. Few other factors will have as great an influence on the success of the mobility transition as the decarbonization of the truck sector. The process of moving to a carbon-free long-distance logistics may seem complex at first glance, and the level of investment needed may act as a deterrent. However, numerous studies have shown that a Europe-wide charging infrastructure can be introduced quickly if the right mechanisms are in place.

This pan-European initiative is essential for the success of electric vehicles in the transport sector. By the end of this decade at the latest, the number of low-emission and zero-emission trucks that can operate in Europe will be determined or limited primarily by the available infrastructure. The shift will not happen overnight. It will be a gradual, sustainable process that will take place at the same pace as the necessary expansion of the power grid. Unless charging stations are available all over the continent, the system will not work.

Competitors become partners

Without a sufficiently dense, efficient, and resilient network of charging points, haulage companies and large retailers will simply not invest in new vehicles with electric drives or begin the transition process. The German National Centre for Charging Infrastructure, which forms part of the state-owned company NOW GmbH, takes a similar view of the situation. “The rapid expansion of the charging infrastructure for commercial vehicles is necessary to provide a fuel supply for the trucks that have already been announced by the manufacturers,” says Johannes Pallasch, spokesperson for the center.

In order to resolve the chicken-and-egg problem of e-mobility, truck manufacturers are trying to get ahead of the game. The industry, in the form of the three leading producers of commercial vehicles, has acknowledged its responsibility. The TRATON GROUP has entered into a joint venture agreement with Volvo Group and Daimler Truck to give the expansion of the infrastructure a much-needed boost. Companies that are otherwise fierce competitors are plan working together to pave the way for a zero-emission future. The creation of the joint venture is subject to regulatory approvals.

The partnership is scheduled to start operations in 2022 following completion of all regulatory approval processes. They plan installing and operating at least 1,700 fast-charging points supplying renewable energy on and near freeways and at logistics hubs and unloading points. The specific goal of the project is the decarbonization of long-distance freight transport, and the companies involved initially plan to invest a total of €500 million.

Master plan for charging

One key advantage of truck transport is its predictability. In contrast to the erratic combination of commuting, shopping, and weekend outings that cars are used for, a significant proportion of commercial vehicles follow regular routes with predictable loading and stopping periods.

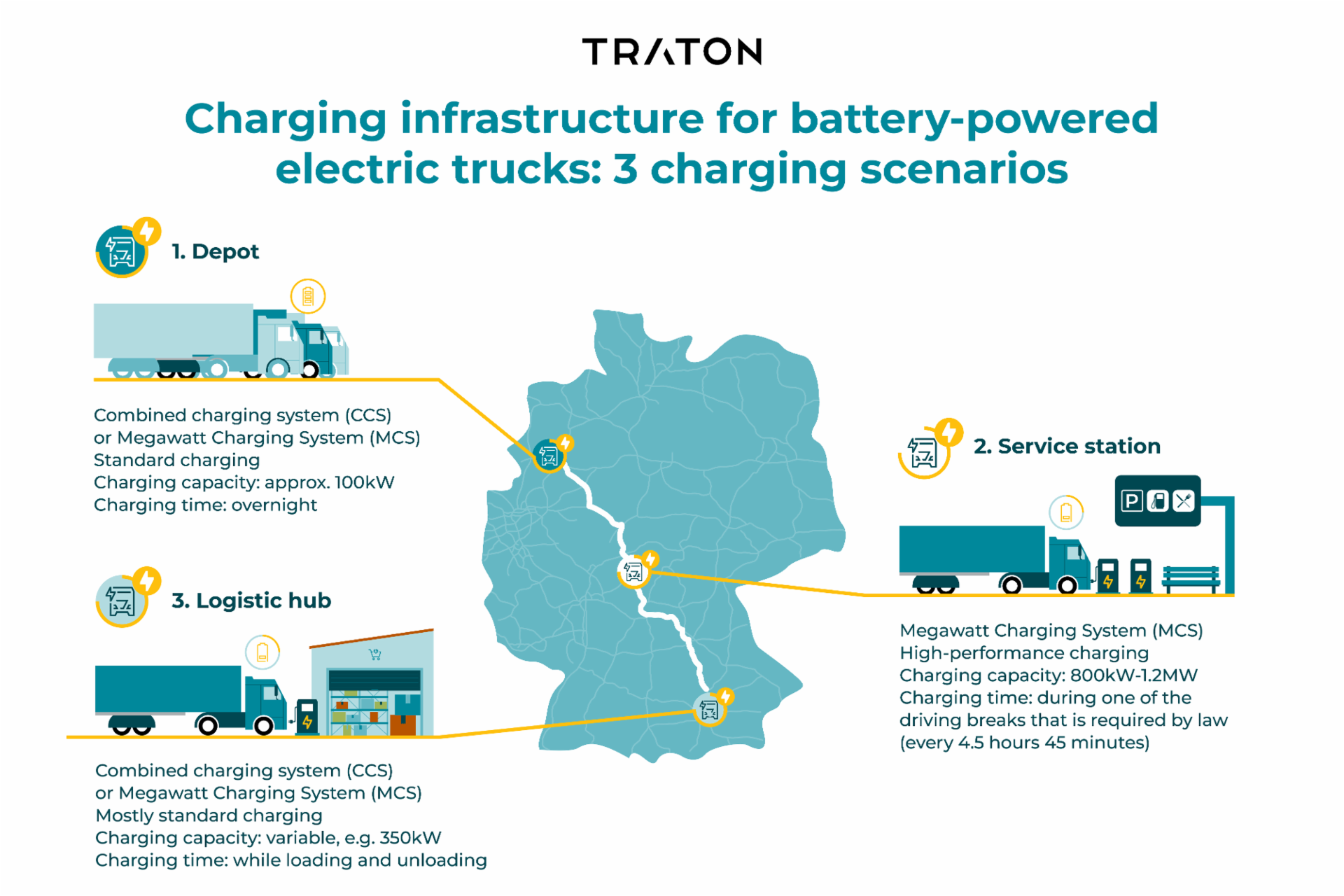

The most common charging scenarios for trucks are, therefore, different too. Private EVs are often charged in public spaces and, as a result, charging points need to be installed by the roadside or in public parking lots. Heavy goods vehicles may be charged at rest stops near freeways, but the majority of the charging processes take place overnight in the company depot or while the trucks are being loaded or unloaded in logistics centers.

According to Andreas Kammel, who is responsible for the electrification strategy at the TRATON GROUP, this results in “a much lower load on the grid than one might assume.” On the contrary, trucks can actually help relieve the stress on the electricity grids. “Long-haul trucks are typically topped up around noon when plenty of solar energy is available and the grid operators do not know what to do with it. By contrast, at night while charging in the depot or at the rest stop on the freeway, the demand for electricity is low. In most cases, we will be able to avoid the times when electricity is expensive and the strain on the grid is high, such as in the early evening.”

In addition, legislation requires truck drivers to take a 45-minute break after four-and-a-half hours of driving time. Both the drivers and their trucks need to recharge their batteries.

“During this time, a fast-charging point can supply the battery of the truck with enough energy for the second half of its route,” says Andreas Kammel. “Provided, of course, that the necessary infrastructure is in place.”

Cross-border efforts are needed

Studies show that the predictability of the routes means that the available range of electric trucks is “often already sufficient for local and regional journeys.” For example, an investigation carried out by the NGO Transport & Environment indicates that it would already be possible to electrify 60% of the truck fleets of large freight forwarders and trading companies. The task now is to exploit these strengths in order to make use of the potential of battery electric vehicles for long-haul transport.

In addition to the private charging infrastructure, public investment is also needed. The transition to e-mobility can be successful if the appropriate subsidies are put in place. As long-distance freight transport often operate on cross-border routes, cooperation between governments is required for the expansion of the public charging infrastructure. “Battery electric long-haul trucks will soon be here. The technology is already available, and the grid operators are cooperating. What we now need is the political support for the rapid, massive reductions in CO2 emissions that are possible with this technology. For this reason, we must push ahead quickly with the introduction of a high-performance charging network for e-trucks, including public funding,” says Catharina Modahl Nilsson, CTO of the TRATON GROUP, summing up the current situation.

“Augmenting the expansion of the charging infrastructure for electric cars, megawatt chargers for trucks should be installed as well.”

Catharina Modahl Nilsson, CTO of the TRATON GROUP

In the European Union, the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) aims to establish a standardized, mandatory framework for the subsidies for electric heavy goods vehicles. Of course, this also includes the charging infrastructure. Although many experts from the industry and from the field of research see the proposal as an important first step in the right direction, they also agree that it does not go far enough to allow for competitive operation.

The regulation must be tightened up

The concern is that the pan-European vision is not being turned into reality quickly enough. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA), for example, has published a position paper that expresses its “serious concerns” about the “lack of ambition” of the current regulation. Other stakeholders refer to a “promising starting point” that still needs “tightening up.” “Augmenting the expansion of the charging infrastructure for electric cars, megawatt chargers for trucks should be installed as well,” says Catharina Modahl Nilsson.

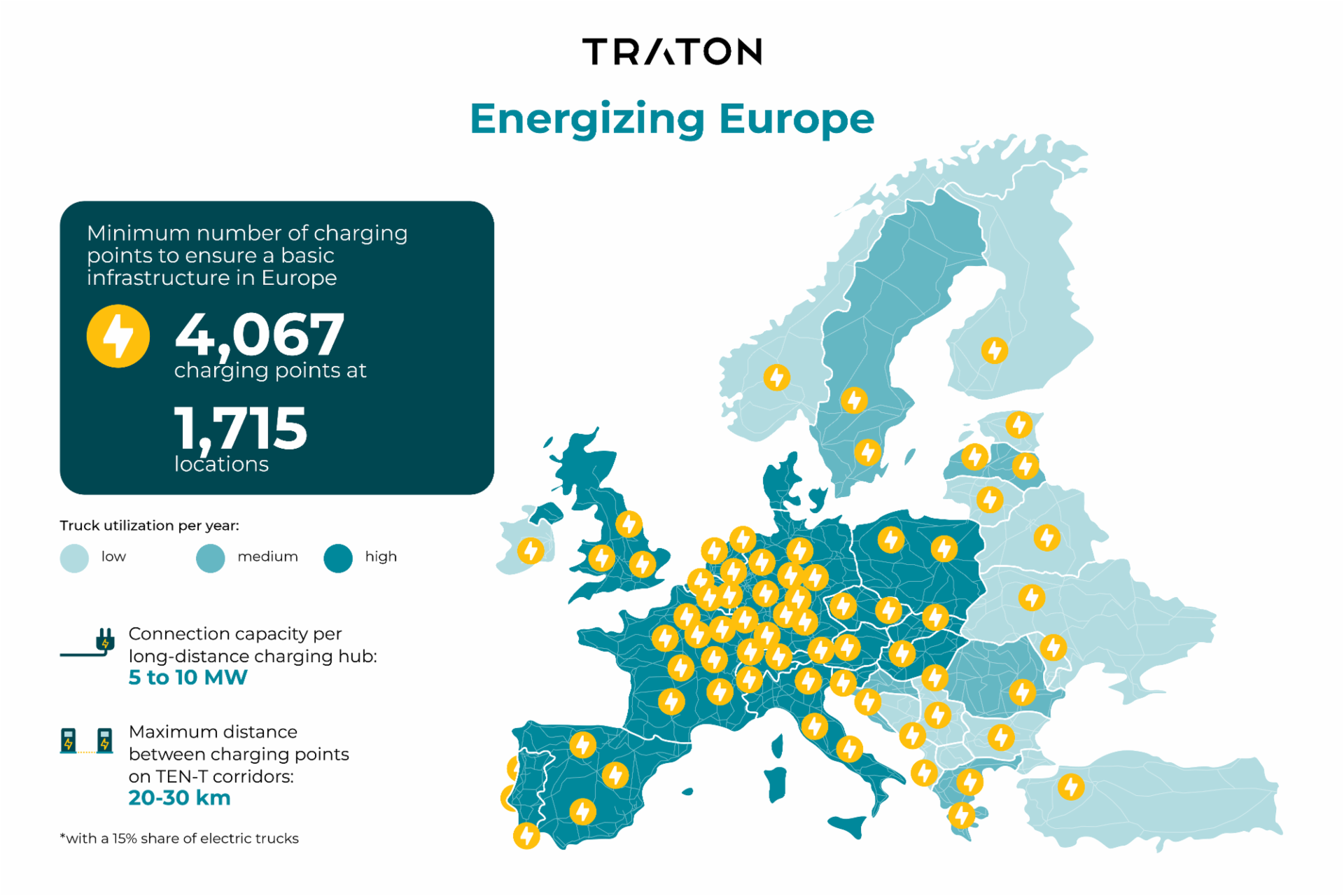

A particularly important consideration is the charging infrastructure on the trans-European transport corridors, a road network covering thousands of kilometers and stretching from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean and from the Atlantic to the Balkans. This is where the planned intervals between the individual charging points must be reduced. An ideal distance is 20 to 30 kilometers. On other, less busy long-haul routes, an interval of 50 kilometers will be sufficient. The output of each truck charging station should reach between five and ten megawatts during the current decade.

In simple terms, it is up to governments to provide the necessary subsidies for a charging infrastructure that meets the industry’s needs and to put the infrastructure in place, because the manufacturers are ultimately being called on to bring about a huge reduction in the CO₂ emissions of their fleets. To put this in perspective, a conservative estimate by the Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research (ISI) shows that we need at least 4,000 high-performance charging points at around 1,700 locations across the entire continent by 2030. This figure is based solely on the mandatory program to reduce CO₂ emissions. The pressure on margins in the market could increase the requirement significantly.

The freeway becomes the laboratory of the future

Let’s go back to the A2. The 500-kilometer stretch between Berlin and Dortmund is not only one of the main routes for the European logistics industry, but also a laboratory of the future. It is here that the cross-industry high-performance charging project (HoLa) is installing and operating two fast-charging points at each of four locations under real-life conditions. The trial is all about acquiring knowledge. The aim is to “integrate suitable locations for electric trucks into logistics processes at an early stage and to obtain experience of using the innovative fast-charging points for the trucks,” explains Patrick Plötz from the Fraunhofer ISI, who is leading the HoLa project.

The trial on the A2 involves not only the research institution but also several stakeholders from the private sector, such as energy companies, grid operators, truck manufacturers, and rest stop firms. It is already obvious that for the mega-project to be a success, in the future everyone will have to pull together in the same direction.