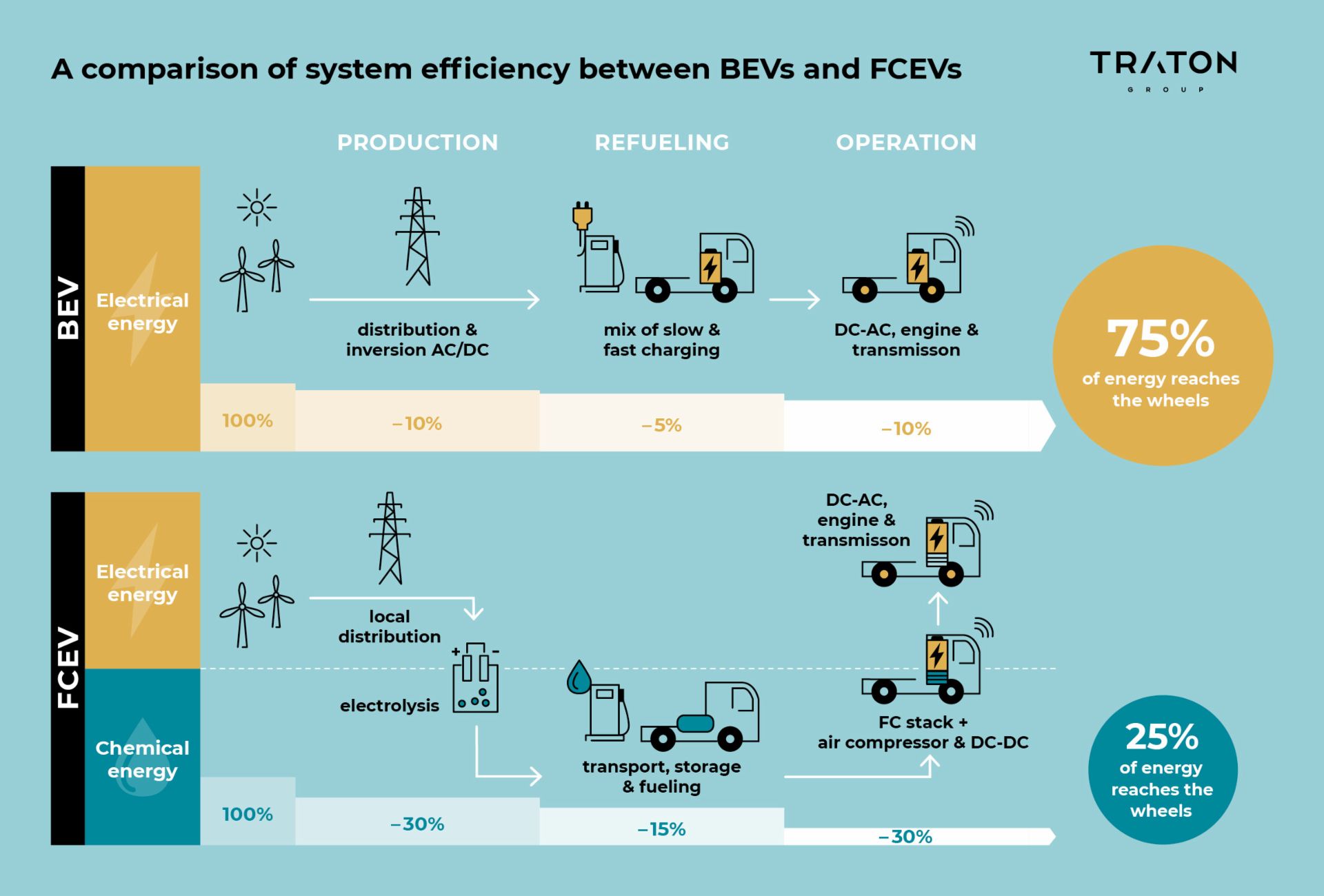

Diesel trucks have dominated our roads for over a century. However, given the enormous quantities of CO₂ produced by the transportation industry, the era of fossil fuels has to end — and it will end. But what comes next? Two major candidates are commonly discussed: battery electric and hydrogen-powered vehicles. A lot is being done to promote hydrogen at the moment. At TRATON, one of the world’s leading commercial vehicle manufacturers, we also reckon with Europe’s transformation into a hydrogen economy — especially in hard-to-abate industries like steelworks. Yet for the majority of trucks, especially also long-haul trucks, pure electric applications will come out on top as the more cost-efficient and eco-friendly solution. This is because there is one crucial thing holding hydrogen trucks back: just about one quarter of the energy output is ultimately used to power the vehicle, with the other three quarters lost in the conversion. For electric trucks, it’s the opposite.

And even though hydrogen can be imported — for example, a pipeline can be used to transport it from an high-efficiency solar-wind hybrid plant in North Africa — the associated reduction in production cost will still not be enough to offset the higher energy costs that result from this efficiency disadvantage. Thus outside of regional niches, even a production cost of €1 per kilogram of hydrogen that some studies expect can quickly turn into a price of €4 per kilogram at the pump. Achieving this price in sufficient quantities and across the whole of Europe will be especially challenging: steelworks alone require more green hydrogen than there is currently planned production capacity by 2030. Plus, in the long run, hydrogen is unlikely to escape similar fees as the ones already payable on diesel and electricity.

However, even at a price of €4 per kilogram, hydrogen trucks would not be able to compete with electric trucks. This is because trucks are heavily used capital goods that are much more expensive to fuel than they are to acquire. The more electric trucks are being utilized, the bigger their energy cost advantage becomes. And just like that, the common conviction that hydrogen trucks are something for the long haul and electric trucks are just to be used for short-haul application starts to fall apart. How cost-efficient and competitive an electric truck is comes down to constant, heavy usage, not the distance it travels. This is where long-haul heavy-duty transportation comes in.

In total, a typical heavy-duty truck in Europe is already likely to reach cost parity with its conventional diesel counterpart by 2025. A double-digit percentage saving is possible by 2030, increasingly marginalizing diesel trucks economically, too. However, this will only happen if a comprehensive network of fast-charging stations has been put in place that leverages the 45-minute rest period required by law after driving for four and a half hours. The charging itself does not even need to be expensive. Users don’t care about the absolute infrastructure costs, but the costs per kilowatt-hour of electricity — and these are determined primarily by the utilization levels of these chargers. Unlike less cost-efficient passenger car fast chargers, which have extreme vacation peaks to cater for, truck chargers have the advantage of more constant and plannable traffic volumes.

Yet most studies on the trucks’ future are carried out for customers from the hydrogen industry — and many of these studies underestimate electric trucks. Coming from passenger car models, these studies often fail to take into account mandatory rest periods, let alone consider fast charging, yielding costly batteries and payload losses. The assumption that trucks would use pricey household electricity as opposed to cheaper commercial rates is also a common one. And time and again, the potential of batteries is being underestimated: batteries have already reached the prices and durability that some of these studies only expect post-2030. Crucially, all of these assumptions are objectively falsifiable, which would quickly turn the slight advantage of hydrogen trucks these studies see into a strong lead of electric trucks. This is by no means an academic question. These studies influence what type of infrastructure gets built: electric charging stations or hydrogen fueling ones. It is a decision worth billions.

At the same time, even extremely cheap to produce and widely available green hydrogen would not necessarily favor hydrogen trucks, as it would also come in handy as energy storage: to couple supply and demand peaks, and even to feed electricity back into the grid, especially when the excess heat can be leveraged via heat coupling. In turn, this could significantly lower relevant electricity prices, driving up new sales of not just hydrogen trucks, but also and especially of electric trucks. On top, even with conventional batteries, a non-stop range of 1,000 kilometers is a feasible long-term prospect. And with a bit of luck, solid-state batteries will be ready for series production by the end of the 2020s, potentially allowing a full recharge to occur within just ten minutes, much like refueling a diesel truck. This does turn electric trucks into the mainstream solution for the current decade, but more so still when looking ahead to the more distant future, as they will even increase their lead over their hydrogen counterparts. A lead which manifests itself in terms of cost-effectiveness — and hence the price of every single yogurt on supermarket shelves — but also the trucks’ carbon footprint. Given the right storage infrastructure, the same wind turbine could power three times as many electric as hydrogen trucks. At the same time, well over 90 percent of the batteries could soon be recycled again and again with only moderate energy input.

Even if the electricity mix were to remain the same, few alternatives to the introduction of electric trucks would yield such high CO₂ savings from such low levels of investment. Last but not least, the precious hydrogen fuel could then be freed up more for harder-to-abate industries and could, for trucking purposes, be used much more consciously. Pure electric trucks, for example, are best suited to constant long-haul usage, but are less efficient when they need to be deployed sporadically and flexibly. Hydrogen can then be leveraged — for example as a “range extender” — as long as charging infrastructure isn’t ubiquitous. Regions where hydrogen is particularly cheap should also have a part to play, among others around North Sea wind farms or at major ports.

All of this means that although hydrogen trucks will take hold in a growing number of market applications over the next ten years, they will lose more and more ground to — increasingly practical — electric trucks, simply because the latter are cheaper to run. Drawing a parallel with passenger cars further reinforces this point. Whoever considers electric cars to be the future of mobility should have all the more reason to believe in electric trucks, which offer an even better case across the board with much lower electricity and fast-charging costs and more regular, intensive use, thus also more quickly amortizing their initial carbon footprint. Hydrogen will play a major role in all of our lives. But it is not the be-all and end-all for sustainable road transportation. Especially when it comes to long-haul trucking, the future is purely electric.